Ah, such an innocent question. Asked with nothing but the purest intent – to show interest in your friend and what they’ve been doing. After all, you’ve been to school. You know that college degrees are well-defined walk-ways, concrete paths marked with courses you must take and exams you must pass, all as you check-box your way down a list of “Degree Requirements” pre-approved by the university. So you figure that your friend has a pretty good idea of where that finish line is and that this question is a way you can show excitement about what they’re doing.

Oh, honey.

You sweet summer child.

You have no idea the emotional turmoil you just triggered.

Don’t feel bad. It’s not your fault. After all –

– this is one of academia’s best kept secrets:

There is no path.

If your friend was like most masochists high-achievers who decide to pursue a PhD, they did so with the same belief. And it wasn’t until they were already in their program, having spent years and hundreds of dollars preparing and applying, uprooted their lives and risked their financial security, and committed themselves to this path, that they learned it, too.

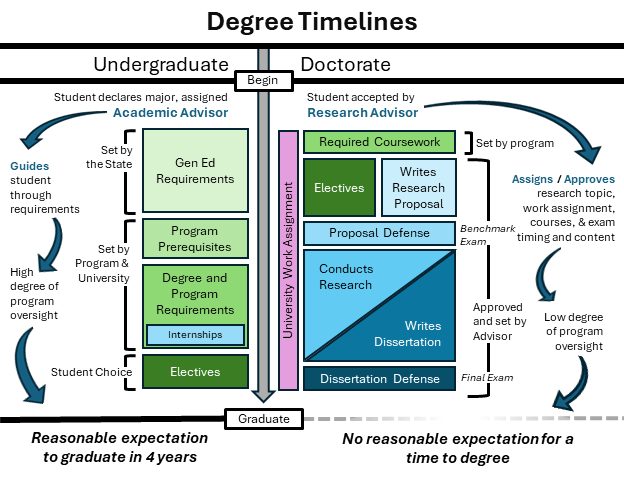

Unlike other kinds of higher education degree programs, PhD programs operate with a uniquely high degree of, shall we say, “independence,” from university oversight. Those who enthusiastically defend this independence – who also happen to be those who successfully traversed it and who continue to benefit materially from it – are quite adamant that it’s Simply Impossible to operate any other way. That each program is so uniquely rigorous, each avenue of research so singular, that any kind of oversight or standardization would stifle progress and make their work as researchers impossible.

While there is no doubt that research programs – which, by definition, explore areas that are not well understood – do need a degree of flexibility in order to operate, that flexibility should come through channels of exception, not default. That there is no standard even for definitions of exams, expectations of research advisor, or role of committee members is astoundingly negligent. There is no reason why universities should not have an approved framework that incorporates the common elements of a doctoral program – a reasonable number of graduate-level courses, attendance at seminars or events, requirements for proposals and exams – as well as processes by which justified exceptions can be granted, for either entire programs or single individuals. But the current modus operandi – that of allowing programs, and usually individual advisors, to have near complete control over whether a student has met the qualifications to graduate – is fundamentally antithetical to it being the capstone degree for a system of formal education. It boldly declares that the peak achievement of formal education is exempt from the fundamental assumptions of the system.

Those who have not had the soul-crushing experience of trying to survive a PhD program might not fully understand the impact that this by-default free-reign can have on a person. This is no doubt partly because, while many of us have had had extremely stressful work environments, we’ve also been protected by employment regulations. These regulations not only help to prevent workplace mistreatment, but they provide an avenue for redress when mistreatment arises. But the majority of the work that grad students must do as part of their program are not protected by employment regulations. This is true even though they are paid by the university and their progress in the program is required in order to have the job. The program itself is exempt from regulation. So not only does this system have very little oversight over what duties are “required” of the students, there are no regulations that protect students from requirements that range from inappropriate to outright abusive. Combine this lack of oversight with the competitive nature of academic research, and you get an environment so toxic that tolerating abuse becomes a de facto degree requirement.

Right now, if you listen closely, you might be able to hear the outraged cries of academics offended at the implication of their engaging in unethical and exploitative behavior – after all, some of them do get quite loud when they yell. But if I had a dollar for every time I heard an irate university admin or faculty go off, I might have made a living wage during my program.

So how does a university determine whether or not a student is qualified to graduate? Well, PhD programs still operate under an “apprenticeship model” of education – but one that hasn’t kept up with the times. Modern trade apprenticeships are heavily regulated by commissions and government entities who license and certify craftsmen as they progress through training. In contrast, academia has held tightly to the medieval form of apprenticeship, in which students tie themselves to a “Master Researcher” (their “research advisor”) who is tasked with guiding them as they gain the knowledge and skills necessary for them to be Independent Practitioners of the Research Craft and earn the title “Doctor”. Research advisors do more than tell students what courses to take. Advisors tell them what research to do, how much to do, and how to do it, and this changes throughout the program; advisors have inordinate control over the jobs that the student is assigned, and this they are often assigned to directly assist their advisor in either conducting research or teaching courses; advisors decide whether the student has sufficiently met the advisor’s standards to qualify to take the exams to progress through each stage of the degree; and advisors approve the individual members of the student’s “Dissertation Committee” responsible for giving them exams.

And what does the Master Researcher (and university) gain in return? Well, cheap labor, of course. Running a research program takes a lot of work – you need people to run lab experiments, do background research, write papers, apply for grants, teach courses, meet with students. Paying graduate students a firmly capped stipend stripped of benefits is a lot cheaper than paying faculty, adjunct or not. And if your advisor also needs help scheduling appointments, picking up dry cleaning, hosting guests, catering meals, sorting through trash for lost items… well, who else better than their apprentice? Master Researchers can’t be expected to do it all themselves, and students who are serious about their program must be willing to put in the extra hours to prove that they are worthy enough to earn the title of Doctor. Not everyone is “cut out” for academia, after all; you have to really want it. You need to prove to them that you’re willing to do what it takes. And your advisor not only allows you to graduate, but they’ll be included on every resume, CV, and job application in your future. You are tied to them for the rest of your career. You need their approval. And if you decide to leave, realizing that this isn’t for you, it hardly hurts the university – there are hundreds of students lined up to take your place at the next recruitment cycle.

I honestly wish I could write about students in grad school without it coming across as a badly written B-movie plot with villains twirling their mustaches as they cackle maniacally. But more than that, I wish that working around-the-clock and being verbally abused for setting any kind of boundary wasn’t such a ubiquitous part of doctoral “training” that students weren’t flooding mental health services, abusing substances, dropping out, and contemplating suicide at rates unheard of any other industry.

I have no doubt that if some of the greatest thought-leaders of our time would only shift the focus of their well-honed intellect from making excuses to making policies, we might actually come up with something that works. At minimum, universities should implement institution-wide policies that mirror those of basic employment regulations. The tired claim that the same kind of regulations that protect millions of employees across thousands of industries would simultaneously cripple research progress at universities is a straw man fallacy of academic proportions.

Pun intended.

Except that it really isn’t funny.

Kaylynne M. Glover, PhD

FAARM Co-Founder

Director of Communications